The Honeybee Year 2011-2012An autobiographical summaryWe have come to consider that our beekeeping year runs from June through the following May because our main surplus flows conclude by the end of May and our plans then turn to managing the hives for the next year. Here, I summarize the past year of our hobby "operation," make a few focussed comments, and lay out plans for the upcoming year, notably to keep only one permanent yard, at our Homestead north of Tallahassee.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

We usually requeen with commercial stock on alternate years; thus, on May 12, 2011, B Weaver queens were installed; they were accepted as the photo (below left, taken Jun 01, 2011) indicates. A subsequent check (June 16, 2011) confirmed that all continued swimmingly with the new queens as well as the overall condition of the hives, as state Apiary Inspectors Billy Langston (lower right) and Jeff Pippin (not shown) demonstrate with a frame of brood. We've used many sources of queens, but have settled with alternating stock from B Weaver and Purvis Brothers. Using stock from these queen producers (and raising from them), we avoid use of all antibiotics, fungicides, and acaricides, though I do sometimes sprinkle powdered sugar into the hives ("Dowda method" for varroa suppression; Tom Dowda). Thus, to the extent that we are able to control, our honey is "chemical free." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At least since December 2001 when the photo (below left) was made, we've continuously maintained a yard at the Farm, where we first placed bees in 1981. (Thanks to Nedra for the decorative painting on the front of the hive!) The Farm yard has been moved around a few times and we have changed our management structure (we no longer use slatted racks, Morse stands, and mainly do not use solid bottoms; most importantly, we stopped using chemicals in 2004). Having bees at the Farm has been a pleasure (more later) but also a challenge. Typically, 3-4 hives (see my account, October 2010)--the minimum sustainable unit in my opinon--comprise the Farm apiary and during the past beekeeping year, two have been lost from pesticide poisoning (June 2011 and April 2012, below right). When those losses come on the heels of a swarm (April 01, 2011--just before the main flow there about May 1), production and indeed the sustainability of the location are in peril. For several reasons-- pesticide poisoning, contamination of my disease-resistant stock with other local bee stock, the nuisance of transport or duplication of equipment, and the prospect of a hobby outgrowing its budget and pleasure--the Farm apiary will be shut down, and our yard at the Homestead will be revamped, but not increased in size (more on this subject in a later post). However, beekeeping is all about location and possibly a hive or so will be moved to the Farm for gallberry (which I favor for dessert ) and goldenrod (which I favor for mead). Some elaboration follows. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Obviously, the production chart at the bottom of the page indicates, notwithstanding my complaints, that we had a positive year at the Farm (better than state average, even with the hives lost to pesticides). Our best hive, which was about equal to the one that was poisoned, was the champion: four full supers of surplus from the spring. The late Mr. Jim Herndon (Florida Apiary Inspector) would have described this hive as "boiling over" (right, taken June 03, 2012). Just seconds after pushing the bees down with smoke, they would re-emerge from the brood nest and cover the top bars. I was exceedingly fortunate to have the few hours that Mr. Herndon and I spent together, and wish there could have been more--we shared an interest in gardening and I was enthralled with his accounts of beekeeping along the Apalachicola River in the old days. Regrettably, that was not to be as he succumbed to prostate cancer. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The tupelo flow at the Homestead ends about the time that the gallberry flow at the Farm begins, which is great timing for me. For example, I started a nuc at the Homestead and expanded it to a full hive body with a super of new foundation during the tupelo flow. This hive didn't have the strength to draw the comb and fill the super with tupelo before the flow ended, but with additional time at the Farm, they packed the frames perfectly with gallberry, giving me more comb in addition to the honey. Note that this comb was drawn, 10 frames in a 10-frame super. If there is a strong flow and a good hive (here, a man-made swarm, but with a young queen), the combs are perfect; otherwise, I intersperse 2-3 frames of new foundation toward the center of 9 frames in a 10-frame super. In summary, and as mentioned, I expect to retreat from our full-time presence at the Farm, but move hives there temporarily from time to time. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

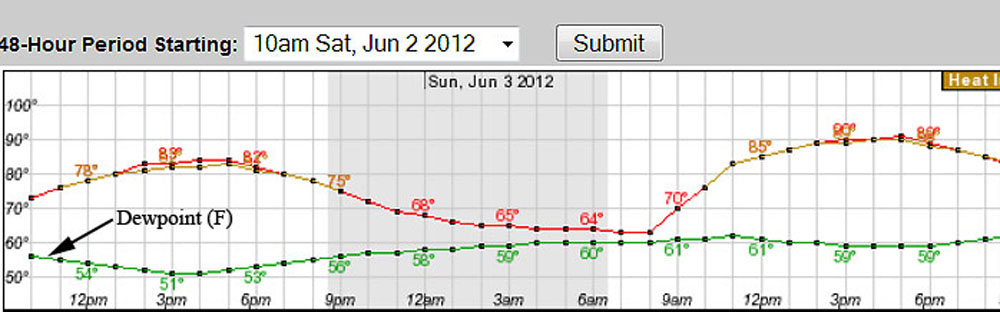

We are in our 14th straight year of bottling honey, and from time-to-time, we have also made cut comb, chunk, and creamed honey. None has ever spoiled. The key, of course, is to keep the water content low (honeys with a water content ≤18.6% qualify for U.S. Grade A and are considered safe). In other words, we have merely replicated the work of innumerable beekeepers around the world over the past few millennia. No bragging rights there. Notwithstanding, I am always concerned about moisture, living as we do in the very humid south. I hesitate, though, to make an extended comment. I do have a tendency to not let well enough alone (about my writing, Shuqiu Zhang once said, "You draw a good snake, but then don't stop without adding legs."). My writing has always had a tedious quality, I think, an effort to immunize myself against criticism over facts. In this regard, one Saturday morning stands out. I was working on a paper with my fourth and final academic mentor, Oliver Lowry, at his home in Ladue, MO. I presented with a paragraph of reservations, caveats, denials and doubts. After studying it for a moment, he looked at me and said, "You mean, in broad terms, . . . ." He had captured my lengthy convoluted construction in one brief sentence of small words and I immediately realized he was right. Looking back, I am further humbled to recall that I myself was by then an anonymous peer reviewer, receiving manuscripts from my senior colleague Joe Varner. I was not up to task, and, really, young reviewers should be mentored, too. I hope I improved in writing reviews over the years and regret any harm my earlier reviews might have caused authors. So, trying to learn from my mistakes, here I will stick with basic general notions, though a little unhappily and dismayed that I skip details (even conceptual concerns). Water deserves more, but for another day. The basic observation is that bees fan dilute nectar, drying it hopefully until the osmotic potential is too negative for spoilage organisms to grow. Of course, water will only move from the nascent honey to the atmosphere if the event is spontaneous, i.e., ∆G˂0. Similarly, water can move from a moist atomosphere into the honey. An equilibrium chart is shown here (developed, I think, for 80F). In broad terms (thanks Dr. Lowry!), at RH<60%, the driving force will be for water to move from sufficiently dry honey to the air. Calculations of the rates of water movement into or from bulk honey would be prohibitively complicated and probably would provide little specific insight (e.g., the results would be different for thick frames than for thin frames). Suffice it to note that honey in ventilated supers can lose 1% moisture in 24 hours in a warm dry honey house. There are two take-home messages for me. The first is, when possible, harvest the honey after a day or so of low dewpoints. As an example, I selected a harvest time when the forecast was for low dewpoints and high temperatures (chart below, from the NWS). In fact, the dewpoint reached 50F mid-day June 02 and was 60F (RH~40%) when I harvested 3-5 pm the following day. (For reference, a dewpoint of 70F is typical this time of year here.) Thus, the honey could not have gained moisture during harvest. And, I expect the honey lost moisture during the 36 or so hours before harvest (screened bottom boards and hive covers propped open for ventilation). Anyhow, selecting a period of low dewpoints to harvest won't hurt and might help. <continued> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Our bottling station consists of a second-hand stainless steel work bench, which I bought at a farm auction. I was not alone in wanting it and shuddered at the thought of such a nice table having a bloody deer draped across it. It became rather pricey. I made up for it though by obtaining the wall cabinet essentially by "dumpster diving." With elbow grease, Nedra's painting, and updated pulls (a gift from daughter Elizabeth), it serves to hold miscellaneous supplies, such as caps. (I can't buy the caps in bulk, but I inspect each, wipe out the inside, and store in ziploc bags.). The bottler (left bucket) is a standard item, and I made the final straining bucket (right) by replacing the bottom of a food-grade bucket with a stainless-steel sieve, which supports a nylon straining bag into which the honey is poured. The strainer sits on the bottler (upper, right) as I cut the center of a top out and slid the remnant up around the bottom of the strainer (best seen in the upper left). Usually, I let the honey sit in the bottler for several days and remove the bubbles and tiny bits of wax that rise to the top of the honey. With so many different small lots, that care wasn't practical, so some of the bottles, like those in the markets, have suface "debris." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From buckets to bottles! Given the right mood and no schedule, bottling--the culmination of a lot of hard work--is satisfying. Here, the bottles for the season sit on the top of a temporary work bench on top of the syrup kettle/furnace. (Today, this building is the honey house, on another day, the syrup shed . . . .) | Well managed hives at my Tallahassee location can store surplus even in March. The tupelo bloom begins about April 5th and runs for about three weeks. In some years, I put on fresh supers to make this varietal honey (above). Tupelo and sourwood honeys are considered by many to be the best of the nominal 300 varietal honeys produced in the U.S. It is mild, sweet (because of its relatively high content of fructose, a very sweet sugar) and resists crystalization (because of its fructose content). Of course, it commands a higher price and I've seen "tupelo honey" being sold that was clearly not real tupelo honey. (A drop of tupelo on a white background reveals its greenish cast.) This particular lot was taste-tested by Billy Langston ("my" bee inspector and tupelo beekeeper) and declared to be tupelo. Over several years, I have also had carbohydrate analyses conducted, which provided the predictable results. For reasons I can't explain, this year's production fell nearly 2% short of that required for certification (. . . that 50% of the included pollen be tupelo.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I do not sell honey (because of the litigious nature of our society). Still, I like to meet the goals of my "customers." Most commercial honey is heated (to facilitate handling, to inhibit crystalization, to reduce the risk of botulism). Most commercial honey is also filtered (to inhibit crystalization and to make a brilliantly clear product). The downside is that pollen is removed by filtration, and flavor is affected by heating. Heating (and prolonged storage) also markedly increase the HMF content. I will leave it at that. There are some very rude people with unsubstantiated opinions on both sides of the raw vs. processed honey argument. The opinions often seem to line up with pocketbook issues as much as anything. Anyway, I am on the "granola and Birkenstock" side, i.e. I prefer and only make raw honey and leave the next fellow to do as he pleases.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnote 1. Cotton honey crystallizes readily; some crystallization is expected of most honeys, but if excessive, will leave the liquid phase too dilute and susceptible to fermentation. Thus, if not blended, it should be stored frozen in my opinion. The reason that cotton honey crystallizes so readily is its high glucose/fructose ratio, ~1. In my opinion, cotton honey is a nuisance: cotton-honey crystallizes in the comb (shown here after robbing the residual honey following extraction) & free crystals after they had been shaken from robbed comb. Perhaps it will sound bizarre (snooty?) from a beekeeper, but I'd rather not expose my hives to cotton. As an aside, these crystals are more creamy than gritty, having a mouthfeel reminiscent of poorly made divinity. Footnote 2. Nedra, who is not fanatic about honey, volunteered that this was the best she had ever tasted. I don't think I have tasted better, either. However, I enjoy the range of flavors from different honeys. Honey is best stored long-term in a freezer. Botulism Warning: Honey should not be consumed by persons under two years of age. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||