The Honeybee Year 2011-2012

An autobiographical summaryWe have come to consider that our beekeeping year runs from June through the following May because our main surplus flows conclude by the end of May and our plans then turn to managing the hives for the next year. Here, I summarize the past year of our hobby "operation," make a few focussed comments, and lay out plans for the upcoming year, notably to keep only one permanent yard, at our Homestead north of Tallahassee.

We usually requeen with commercial stock on alternate years; thus, on May 12, 2011, B Weaver queens were installed; they were accepted as the photo (below left, taken June 01, 2011) indicates. A subsequent check (June 16, 2011) confirmed that all continued swimmingly with the new queens as well as the overall condition of the hives, as state Apiary Inspectors Billy Langston (lower right) and Jeff Pippin (not shown) demonstrate with a frame of brood. We've used many sources of queens, but have settled with alternating stock from B Weaver and Purvis Brothers. Using stock from these queen producers (and raising from them), we avoid use of all antibiotics, fungicides, and acaricides, though I do sometimes sprinkle powdered sugar into the hives ("Dowda method" for varroa suppression; Tom Dowda). Thus, to the extent that we are able to control, our honey is "chemical free."

Obviously, the production chart at the bottom of the page indicates, notwithstanding my complaints, that we had a positive year at the Farm (better than state average, even with the hives lost to pesticides). Our best hive, which was about equal to the one that was poisoned, was the champion: four full supers of surplus from the spring. The late Mr. Jim Herndon (Florida Apiary Inspector) would have described this hive as "boiling over" (right, taken June 03, 2012). Just seconds after pushing the bees down with smoke, they would re-emerge from the brood nest and cover the top bars. I was exceedingly fortunate to have the few hours that Mr. Herndon and I spent together, and wish there could have been more--we shared an interest in gardening and I was enthralled with his accounts of beekeeping along the Apalachicola River in the old days. Regrettably, that was not to be as he succumbed to prostate cancer.

a

a

The tupelo flow at the Homestead ends about the time that the gallberry flow at the Farm begins, which is great timing for me. For example, I started a nuc at the Homestead and expanded it to a full hive body with a super of new foundation during the tupelo flow. This hive didn't have the strength to draw the comb and fill the super with tupelo before the flow ended, but with additional time at the Farm, they packed the frames perfectly with gallberry, giving me more comb in addition to the honey. Note that this comb was drawn, 10 frames in a 10-frame super. If there is a strong flow and a good hive (here, a man-made swarm, but with a young queen), the combs are perfect; otherwise, I intersperse 2-3 frames of new foundation toward the center of 9 frames in a 10-frame super. (Thanks to Charles Deese for the super shown.)

Generally speaking, we produce only two varietal honeys, viz. tupelo (macro of staminate bloom) and gallberry (clone overview, blooming). Unquestionably, our reference to tupelo is correct: our tupelo honey has the expected and atypical greenish cast, the expected and atypical carbohydrate ratio, and has passed the state pollen analysis. Our argument for the authenticity of our gallberry honey is less persuasive--it has the correct color and was collected when gallberry was the dominant honey plant within foraging range.

In summary, and as mentioned, I expect to retreat from our full-time presence at the Farm, but move hives there temporarily from time to time.

We are in our 14th straight year of bottling honey, and from time-to-time, we have also made cut comb, chunk, and creamed honey. None has ever spoiled. The key, of course, is to keep the water content low (honeys with a water content ≤18.6% qualify for U.S. Grade A and are considered safe). In other words, we have merely replicated the work of innumerable beekeepers around the world over the past few millennia. No bragging rights there. Notwithstanding, I am always concerned about moisture, living as we do in the very humid south. I hesitate, though, to make an extended comment. I do have a tendency to not let well enough alone (about my writing, Shuqiu Zhang--shown here (mid-late 90s) with our GSD Timber--once said, "You draw a good snake, but then don't stop without adding legs."). My writing has always had a tedious quality, I think, an effort to immunize myself against criticism over facts. In this regard, one Saturday morning stands out. I was working on a paper with my fourth and final academic mentor, Oliver Lowry, at his home in Ladue, MO. I presented with a paragraph of reservations, caveats, denials and doubts. After studying it for a moment, he looked at me and said, "You mean, in broad terms, . . . ." He had captured my lengthy convoluted construction in one brief sentence of small words and I immediately realized he was right. Looking back, I am further humbled to recall that I myself was by then an anonymous peer reviewer, receiving manuscripts from my senior colleague Joe Varner. I was not up to task, and, really, young reviewers should be mentored, too. I hope I improved in writing reviews over the years and regret any harm my earlier reviews might have caused authors. So, trying to learn from my mistakes, here I will stick with basic general notions, though a little unhappily and dismayed that I skip details (even conceptual concerns). Water deserves more, but for another day.

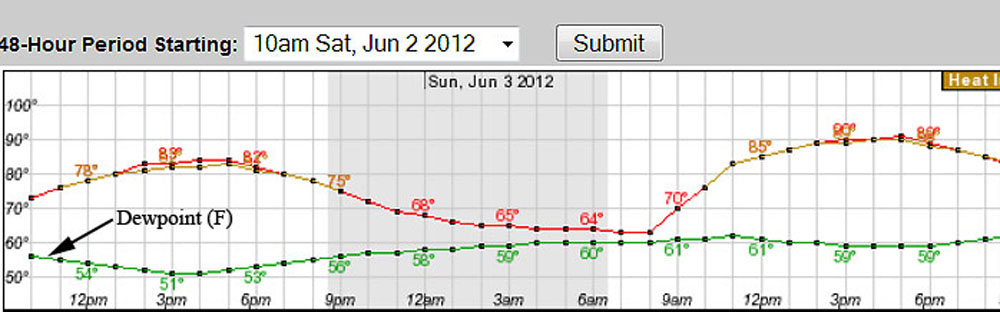

The basic observation is that bees fan dilute nectar, drying it hopefully until the osmotic potential is too negative for spoilage organisms to grow. Of course, water will only move from the nascent honey to the atmosphere if the event is spontaneous, i.e., ∆G˂0. Similarly, water can move from a moist atomosphere into the honey. An equilibrium chart is shown here (developed, I think, for 80F). In broad terms (thanks Dr. Lowry!), at RH<60%, the driving force will be for water to move from sufficiently dry honey to the air. Calculations of the rates of water movement into or from bulk honey would be prohibitively complicated and probably would provide little specific insight (e.g., the results would be different for thick frames than for thin frames). Suffice it to note that honey in ventilated supers can lose 1% moisture in 24 hours in a warm dry honey house3. There are two take-home messages for me. The first is, when possible, harvest the honey after a day or so of low dewpoints. As an example, I selected a harvest time when the forecast was for low dewpoints and high temperatures (chart below, from the NWS). In fact, the dewpoint reached 50F mid-day June 02 and was 60F (RH~40%) when I harvested 3-5 pm the following day. (For reference, a dewpoint of 70F is typical this time of year here.) Thus, the honey could not have gained moisture during harvest. And, I expect the honey lost moisture during the 36 or so hours before harvest (screened bottom boards and hive covers propped open for ventilation). Anyhow, selecting a period of low dewpoints to harvest won't hurt and might help. <continued>

The second message concerns the issue of moisture in the honey house, but details will be postponed until the next report, probably 2014 or 2015. Presently, simply note that consideration is given. We attempt to control humidity and monitor it. If I am particularly concerned, I streak some honey on a dish and determine empirically whether it gains moisture over the course of an hour or so. This is overkill--I take OCD to new levels--but it satisfies my fondness of numbers and being satisfied is the purpose of a hobby; besides, I am on my own time and dime.

In the previous post, we emphasized bottling and as a complement, this one will focus on extraction. After the supers have been harvested and the bees driven from them by smoke, a blower and, finally, a brush, the supers are sealed in a plastic bag. Please note that standard repellent chemicals are not used to clear the supers, and the plastic bags--which can be repurposed later--prevent the honey's gaining moisture and robbers. Back home, the supers are placed in our freezer for at least 48 h or are taken directly to the Honey House for extraction within two days (i.e., shorter than the 4-day guideline). As mentioned previously, our little space for working with honey (merely 330 ft2, much of which is consumed by our syrup kettle, storage, applicances, &c.) is used for several purposes (vegetable processing (mustard Lot 2012-05-01), crush (blueberry Lot 2012-06-08) and fermentation (grape Lot 2011-07-15), syrup making (Lot 2011-11-22)), and there's a good bit of downtime in setting up and taking down. For honey extraction, we make a small work triangle defined by the supers (on the temporary table, below left), the frame-preparation station, and the extractor (a centrifuge). A little bit of honey goes a long way and a tiny amount of wax goes even further, so the floor is covered by a very thin painter's dropcloth. (I don't use any plastic without due consideration, but this is a case in which a little plastic can save a great deal of work, water, and detergent!) A closer view of the frame-preparation station is shown at right, below. Honey from the cappings is drained through the collander into the stainless tub. We generally do not render the wax and make candles--a lot of work--but instead let the bees rob residual honey from the cappings. Click here to see an uncapped frame.

I only have myself to blame when I do not take Nedra's advice. She was strongly in favor of my buying a motorized extractor, but, at the time, I was in my early 50s with yet abundant energy (and also more importantly, my high-anxiety personality goes into a tailspin if I frivously relieve myself of money). Times change, but the extractor is still not motorized (below left). After about 5 supers, it is definitely NAPTIME, which--in a way--is a reward in itself. The other image (below, right) depicts the first step in clarifying the honey, namely, straining through two stainless screens into a bucket. The second screen (not visible) is 500 μm and before bottling, the honey is strained again through a smaller synthetic mesh as shown earlier. We do not filter and remove pollen (indeed, recent Florida law makes it a crime to label a product as honey if pollen has been removed).

btw, the apron was a gift from Nedra, implying our shared interest in Southern Matters. The beautiful sign above the window was a gift of the William Outlaw family.

I close on two positive notes. First, people identify with and are identified by their hobbies, interests and passions. Beekeepers are hardly the exception. Second, most of my life has been spent creating intangible products, particularly research. As gratifying as that is, a hole is still left in my need to produce something of discernable immediate and tangible benefit. The honey chart below speaks to that need.

We hope you have enjoyed this note but emphasize that we don't hold ourselves out to the public as bee experts, just as backyard beekeepers.

Last edit: 2012-11-13

|

Footnote 1. Cotton honey crystallizes readily; some crystallization is expected of most honeys, but if excessive, will leave the liquid phase too dilute and susceptible to fermentation. Thus, if not blended, it should be stored frozen in my opinion.

The reason that cotton honey crystallizes so readily is its high glucose/fructose ratio, ~1. In my opinion, cotton honey is a nuisance: cotton-honey crystallizes in the comb (shown here after robbing the residual honey following extraction) & free crystals after they had been shaken from robbed comb. Perhaps it will sound bizarre (snooty?) from a beekeeper, but I'd rather not expose my hives to cotton. As an aside, these crystals are more creamy than gritty, having a mouthfeel reminiscent of poorly made divinity.

Footnote 2. Nedra, who is not fanatic about honey, volunteered that this was the best she had ever tasted. I don't think I have tasted better, either. However, I enjoy the range of flavors from different honeys.

Footnote 3. p 214, ABC & XYZ of Bee Culture, 40th ed, ISBN 0-936028-01-7.

Honey is best stored long-term in a freezer. Botulism Warning: Honey should not be consumed by persons under two years of age.