An Experience with Hot Bees An Honest Introduction This essay is anecdotal, long, personal, and is in general not written with the audience in mind. You are warmly welcome to read it, but please keep your expectations low, as were my efforts in writing it. Background of my Beekeeping I have kept bees continuously since the late 90s (and for a brief period in the 80s). The relationships among the bees and between bees and their nectar/pollen sources are endlessly fascinating to me. A good time for me is a visit to a hive, watch the bees from the outside, and inspect a perfect brood nest. I respect the rights of bees as my tenants and have not been worried about having them as neighbors. Though I have experienced one serious stinging incident (when I dropped a box full on bees on my unprotected feet), I am not “afraid” of bees, but naturally wish to not be stung and I recognize the danger. My “operation” is based north of Tallahassee, but I have bees at the farm, too. Elsewhere, I provided an account of my 2010 season (and show my back-yard apiary location at the farm). As noted, I take pride in not using chemicals inside my hives (mostly using stock selected by B Weaver ), particularly in Tallahassee where there is no production agriculture within foraging range to my knowledge. Defensive Traits of Bees and Distribution of Defensive Bees Different races of bees have genetically determined levels of defensiveness and beekeepers favor gentle bees for several reasons, explaining at least in part the replacement of the imported German Black Bees in North America. In the midlle of the last century, Professor Kerr deliberately introduced progeny of African queens to Brazilian apiaries, hoping that they would be better suited to the climate. He was aware that they had negative traits such as extreme defensiveness and tendency to swarm often and to abscond, but thought that these traits could be bred out. Resistance to varroa, being undemanding about nest sites, acceptance of low-sugar nectar and other traits account for their success in expanding their range into Texas by 1990. Africanized bees moved into the SE U.S. later than expected, but now they are widespread, and there has been one lethal incident in South Georgia. The spread of honey-bee genes is not limited to natural-range expansion; swarms can hitch a ride on boats and vehicles; queens bred in africanized areas are shipped across the U.S. and even with drone saturation, some africanized drones get their go at it; colonies move across the U.S. and supersedure queens are subject to insemination by africanized drones (the sperm of which, oddly, are highly successful). Jerry Haynes (Am Bee J (2011) 151:439) thinks that there is some evidence of african decendency in bees of all states. Jerry writes regularly for the Am Bee J, is sought after as a speaker, and is the Apiary Inspection Assistant Chief for the state of Florida, so he speaks with authority. Background on my Blood Pressure In my early 30s, I developed labile hypertension when I had a real-pressure-cooker job as an assistant professor at Washington University. I can’t blame WU, though, as I contributed through lack of activity and obesity. I was able to lower my bp through behavior modification until we built our home (“completed” in July, 1989). Nedra was designated as the general contractor and we ourselves did a lot of the work; these are good memories—the four of us and two dogs sleeping in a single room by running power into it after hours, cooking one-pot meals in the workshop, bathing in an improvised shower, children studying in the tent, . . . . I was also running a lab, teaching and wrote nearly eighty reviews that year associated with USDA and DOE. …not to mention, being an editor for Plant Physiology. I wore myself ragged and the situation and I were hard on everyone. However, Will turned out to be a good roofer and Liz, a good plumber’s helper. . . . and, Nedra was good at everything (I am especially proud of how she translated my ideas in product placement—with the exception of sheetrock (which I had no control over) and brick (the debris of which I used in a French drain), all construction waste was removed in plastic bags. Historic low level of waste! Anyhow, my blood pressure went up and I went on medication. The medication (begun in 1989) and exercise program (begun in 1993) kept my blood pressure under control until about 2008. Over-extension and stress (mostly associated with settling estates) resulted in a crisis; after overnighting in the ER with a bp of 215/134, the message got through to me (my father had a debilitating stroke at 54 and his father died at 45 of a stroke). I had a “million-dollar” cardiac workup (by Akash Ghai, whom I heartily recommend) and there was no organic problem. I could continue the path and have a stroke, or I could change and hope to avoid one. Thus, I continued to do my duties at work, but honestly, I didn’t jump in with both feet at each new opportunity (and retired in 2010). I made estate settlements for expediency (not merit), but what is money compared with a lifetime disability? I also started monitoring my blood pressure, both as a means of being aware and as a means of holding myself responsible. The Essence: Hot Bees at the Farm In early April or late March, 2011, Joe Matthews visited me at the farm and we went to take a look at my bees because he was interested in beekeeping and mead making. We were 50 ft (perhaps more) from the hives when Joe was stung and I accumulated 4 stings to my head. . . . surprising, but one incident does not define colony. However, this pattern continued: on one occasion, I was stung in the side yard by the well, again more than 50 ft from the apiary. On another time, the bees pursued me into the cabin, and waited outside the door for me to leave. Clearly, something was awry. I suspected I knew which colony it was, and when I inspected it, the bees literally covered my veil, even obscuring my vision. Several got inside my veil, making their mark. I went into our workshop--agitated bees are not inclined to follow one through a small door into a dark area--and vacuumed off 100s, if not 1000s. I have been around africanized bees in Brazil (about which I published in the Am Bee J 140:401-404), and the farm bees were immeasurably more defensive. Without a hint of hyperbole, they could be called killer bees--they were that bad, and, as alluded to, changed my perspective. |

|

|

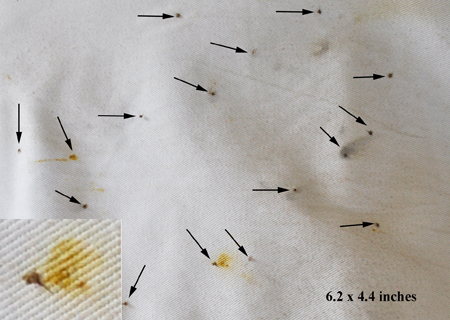

Starting around 8 pm, April 10, 2011, I moved the bees away from the backyard. They had faced east in the backyard, and I moved them about 400 yards and faced them south. One by one, I first sealed the entrance, disassembled the hive (too heavy with honey for me to lift as a unit), put the hive on my RTV and relocated it. Just so it is abundantly clear, this hive moving is not in the same league as driving up to a pallet with a Bobcat and lifting the pallet onto an 18-wheeler. I first moved the two distal colonies (the least likely location for the homeless foragers to enter), and that went without a hitch. I moved the third hive, and it went ok, sort of. As always, I save the worst for last, and I certainly called it right. The final hive was closest to the missing hive (thus picking up the hot foragers) and it was the most populous (to deter swarming, I had made it a double deep with sealed brood from other hives, including the hot one). All Hell broke loose, again. By that time, I was tired and sweaty—stingers can penetrate a clingy wet bee suit. Pure misery. The image to the left was a patch from my bee suit; the arrows indicate stingers. The picture pretty well summarized what the bees would like to have done to me. Of course, the bee suit was protective; else, I might have gotten a dangerous dose. Still, a clingy wet bee suit, as mentioned, doesn’t do the whole job. After the move, I talked to Spouse, who asked the rhetorical question: were you stung? The silence prompted her to ask a more reasonable question. I honestly don’t know how many times I was stung, maybe 20, maybe 50, times. On my left shoulder alone, I counted 6 whelps. I got nailed in tender painful spots, too (especially, the inside of my upper thigh and my neck). . . . creative cursing. It was good I was alone, because I feel sure that some of my passages would have been offensive even to a toothless tattooed old sailor. |

I was relieved to have the move over, but a little uneasy about the number of stings I had gotten so I monitored my blood pressure. The left panel (a thumbnail, solid symbols) is a composite record of my blood pressure measurements made the week before and the week after the move (recall, 2011-04-10). The average was 120/67/63 (systolic/diastolic/pulse), and obviously much of the variability can be accounted for by time of day somehow, with morning and afternoon/evening pressures differing by ~8 mm Hg. Of 62 usual measurements, my highest systolic pressure was 144 mm Hg (10 am) and the lowest was 99 mm Hg (8 pm). Only 2 diastolic values were as high as the 80s, but several were in the 50s. Readings in the right panel (hollow symbols) were taken from 1022 pm until 1250 am (the move concluded at about 10 pm). It is a little worrisome that my pressure dropped to 95/48. (Usually, when my diastolic drops to the mid 50s, I begin to feel it.) |

|

|

The New Location and Clean-up Everyone knows that hives should be moved less than a couple of feet or more than a mile. Unfortunately, that was not possible, so many of the foragers did not re-orient to their new location. They left home, collected nectar, but did not notice that their hives had been moved. They returned to the old location, and finding nothing, had hissy fits. I spent the entire day killing the disoriented foragers (this was one time that I was thankful that bees are easily killed with Sevin). A wholly miserable day to follow up the night of moving. I figured that I killed so many foragers that the hives would be devastated, but that was not completely true. I wound up with a strong hive (the only one to make much of gallberry), a pretty good hive, a weak hive (which I have a queen coming for), and a drone-laying hive (which miraculously straightened itself out, but I requeened anyhow). But, they are all gentle enough to work with, and I have since harvested more “wildflower” (previously, I’d taken 3 supers so far from them this year). |

Perspective Well, this was not fun, and if it happens again, I will go out of the beekeeping business. Becoming beeless will change who I think I am, but the pleasantness of having bees will be gone. The take-home message of this cautionary tale, though, is that the world of bees in South Georgia has made a serious turn. From now on, I will always approach any colony as if it has become africanized, I will look more carefully at potential nest sites before barging through, and I won’t recommend that anyone keep bees in an urban setting, which I know will be an unpopular input to some. Last edit 2011-05-20. |

|

Return to Documentation for this page. |

|